November may go down as the shortest month of 2020. Somehow the act of refreshing the Google result for “election winner” every five minutes for a week really opened a time wormhole that skipped over half the month and landed us here: December 2nd. Joe Biden is president-elect, COVID-19 cases in the United States are about to surge, and Spotify dropped their jolly annual feature Spotify Wrapped.

Spotify Wrapped crunches all the user data on the platform for the previous calendar year and packages it an animated slideshow with categories such as Top Songs, Top Artists, and the new addition Top Podcasts. As previously covered in my last newsletter, Spotify’s business model is increasingly reliant on podcasting, so it makes sense for the service to remind users that they can stream their favorite podcasts alongside their tunes. When you are done reading this newsletter, I highly recommend Liz Pelly’s piece in The Baffler “Podcast Overlords” on Spotify’s goal to manifest destiny the podcasting world.

The playlistification of podcasts is already proving to have influence on the types of podcasts Spotify recommends, similarly to how mood and moment playlists have dictated what types of songs rise to the top. Spotify has tightened its control over what wins and loses, and over time it has spawned various waves of music manufactured with specific playlists in mind, resulting in something more like platform culture than music culture. Within podcasting, playlists like “Your Daily Drive” and “Daily Wellness” are already suggesting that over time streaming platforms could come to affect the creative process of podcasting by way of what is preferable in its flagship playlists: shorter podcasts, or those with chilled-out undertones, or ones that otherwise play into listener vulnerabilities.

As I’ve explored in previous Transmission installments, “official” playlists encourage passive listening, an experience defined more by mood than by artist or song. This commodifies music and effectively reduces it to muzak, or generic retail brand elevator music. When the concept of playlisting is applied to podcasts, passive listening is inevitable. What was once an active decision of a consumer choosing to listen to a specific podcast has been bastardized into a never-ending stream of quick-bite audio content. The individual podcaster is a single voice in a hoard; and thus, infinitely replaceable. It doesn’t matter who is delivering the 60-second daily financial news podcast—by the time you realize the host is different, “Blinding Lights” by the Weeknd is playing.

Anyway, bookmark that article. We have more to discuss regarding Spotify Wrapped. While flipping through my listening habits of 2020, I stopped on the Top Genres tag.

That is not a typo. I listened to THREE-HUNDRED-AND-TWENTY-TWO genres this year, including ONE-HUNRED-AND-SEVENTY new ones. Isn’t that insane? I am a cosmopolitan renaissance man living in the Athens of America, experiencing music so unbound by reality that it encompasses THREE-HUNDRED-AND-TWENTY-TWO different forms of classification. If you asked me to name music genres, I would probably tap out around fifteen, and start making up words hoping my natural charm and confidence would convince you they are real styles of music.

How is this possible? Are there really more than three-hundred genres of music? It turns out the answer is YES, and the answer lies with the data alchemist Glenn McDonald, whom I had the pleasure of meeting during my time in college.

Every Noise at Once

Glenn McDonald has created the mind-bending website everynoise.com, which maps all recorded music available on Spotify on a scatterplot categorized by genre. As of today, there are 5,071 unique music genres, from Czech Classical Piano to Latin Tech House. The y-axis of the plot tracks organic vs. mechanical sounds, while the x-axis tracks atmospheric vs. “bouncier” sounds.

Pretty overwhelming, huh? Clicking any single genre “zooms in” on the scatterplot to reveal associated artists. The result is both fascinating and humbling. You can nearly witness the Spotify algorithm in action: Ariana Grande, Selena Gomez, and Kygo form a tight triangle under the “Pop” category. Not only are these artists featured together on playlists, they are mere pixels away from each other on Every Noise at Once. On the navel-gazing side of things, it turns out I don’t have an eclectic taste in music. The Menzingers, Iron Chic, and Lemuria are not foundational building blocks to Nick’s personal music universe—he just likes Alternative Emo. Thanks Glenn, for revealing that my entire personality can be whittled down to a line of code. At least I have other unique interests like craft beer and old sci-fi novels.

I have spent days staring at this scatterplot, wasting hours pouring over individual genres of music. What differentiates “Indie Rock” from “Indie Pop” and “Indie Punk?” Which artists are snubbed from categories like “New Jersey Melodic Punk?” All of my questions suddenly had quantifiable answers and all the nights I spent arguing whether or not Bruce Springsteen was Punk were rendered moot. According to Every Noise at Once, The Boss is loosely associated with “Protopunk,” “Dance Punk,” and “Post-Punk,” vindicating me after all these years.

Beyond trivia and billion-dollar algorithms, what does the average person gain from this many genres? No one in their right mind would drop “New Wave Speed Metal” as their favorite genre of music at a corporate icebreaker (however, I highly encourage it). Nothing stops a conversation dead in its tracks like a deep-cut music genre. In 2015, I went on a first date with an American who “only listened to Italian Hip-Hop” and had “no interest in mainstream music or television.” There was no second date, but I did use EveryNoise to see if “Italian Hip-Hop” lived up to the hype (it did not).

5,071 unique genres of music is simply too many for us plebs. I suggest we narrow the entire spectrum of music down to a reasonable number of smart, simple, and practical classifications: two.

The Two Genres

There are exactly two genres of music under which all of these meaningless and complicated subcategories fall. These genres are binary, and there is no crossover between the two. They are Yin-and-Yang, Day and Night, Vermont and New Hampshire—we cannot understand one without knowing the other. In Isaac Asimov’s novelette “Nightfall,” the inhabitants of a perpetually-sunlit planet have no concept of night, and when darkness finally comes by way of an eclipse, they are all driven mad (I wasn’t kidding about the sci-fi novels). In the same way, the two genres must be understood as a pair, but I will attempt to define them individually first.

Pop Music

Pop Music, or “Popular Music” is the form of music we interact with most, if not exclusively. It is music commodified in the marketplace in the form of streams, digital downloads, records, live performances, etc. This classification is not determined by commercial success, as the capitalist music industry defines our understanding of “mainstream” music. A famous record in 2020 sounds nothing like its 1950s counterpart, yet they are both considered Pop. It is not sound or style that defines our current understanding of Pop music; instead, we rely on streaming data and sales to guide our ears. So the Pop genre as understood today is not a form of music, but a measure of commercial success.

Think about lesser known artists that sound similar to the biggest stars of today, Caroline Polachek or Glass Animals, for example. They are definitively Pop artists, but because they have not achieved the same revenue totals as an Ariana Grande or The Weeknd, they are relegated to the “Indie Pop” minor leagues. There is nothing indie about either of those artists: Polachek released her 2019 album Pang with Sony Music, and Glass Animals is signed with Universal Music Group. “Indie,” therefore, is also less of a musical descriptor than a measure of sales and monetary success.

The only reason Metallica isn’t being spun on New York’s Z100 radio station is because they are not selling or streaming enough with the station’s target demographic. If a trash metal band thunders on the scene in 2021 and captivates the hearts and ears of millions of young adults in America, Z100 will play their singles, and they will be considered Pop.

“Rock” faces similar problems with genre classification. I’ve written about the plague of Rockism in a previous newsletter, which is the gatekeeping that continues to ravage the genre, preventing its natural evolution and the adoption of modern production techniques. Rock’n’Roll was “Pop” music in the 1950s and 1960s, but diverged from mainstream dominance somewhere in the 1970s. With the emergence of disco, Rock positioned itself in the market as the alternative, and began defining itself against Pop music. Of course, this was coupled with the unspoken assumption that Rock was dominated by white men, excluding The Isley Brothers and Linda Ronstadt from the ranks. Today these artists are known respectively as Soul and Pop/Country artists, but their catalogues belong alongside Rock powerhouses like The Eagles.

Gatekeeping remains a problem with Rock to this day, which has made the genre culturally obsolete. Is Rock a specific sound, or white guys with guitars? If Imagine Dragons is the Billboard Top Rock Artist of the 2010s (spoiler, they are), then I’m not interested in being a Rock fan. Artists today are blending sounds and styles, making it impossible to fit them into a neat little box. If there are 5,071 genres, there is nothing stopping every single artist from existing as their own hyper-specific genre. Is 100 Gecs Pop? Electronic? Rock? Ska? Who knows—it’s just 100 Gecs.

As genres are increasingly being defined by commercial success and artist demographic identity, we are approaching the point where these micro-classification tags are irrelevant. We are living in a post-genre world, where everything is simply commodified Pop music. Rap/Hip-Hop is mainstream Pop on every radio station in America, Classic Rock is just Pop music for dads, and Jazz is Pop for people who pretend to enjoy non-standard time signatures. If it can be commercialized, it is Pop.

There is a discussion to be had surrounding pre-1900s music, before the modern music industry. Could artists like Mozart and Bach be Popular under this definition if their works weren’t sold or commodified during their lifetime? It would be ahistorical projection to apply our current understanding of the music industry to these careers, but today we certainly can classify these artists as Pop, because their works are continually being performed, sold, streamed, and licensed.

Noise

This is where things get weird. You are probably thinking, “Nick, if everything is Pop, then what is the other genre? What are the sounds that balance out the Yin-and-Yang metaphor you’ve set up?” The answer is Noise. No, not “Noise Rock” or “Noise Pop” or even “Industrial Noise,” just Noise.

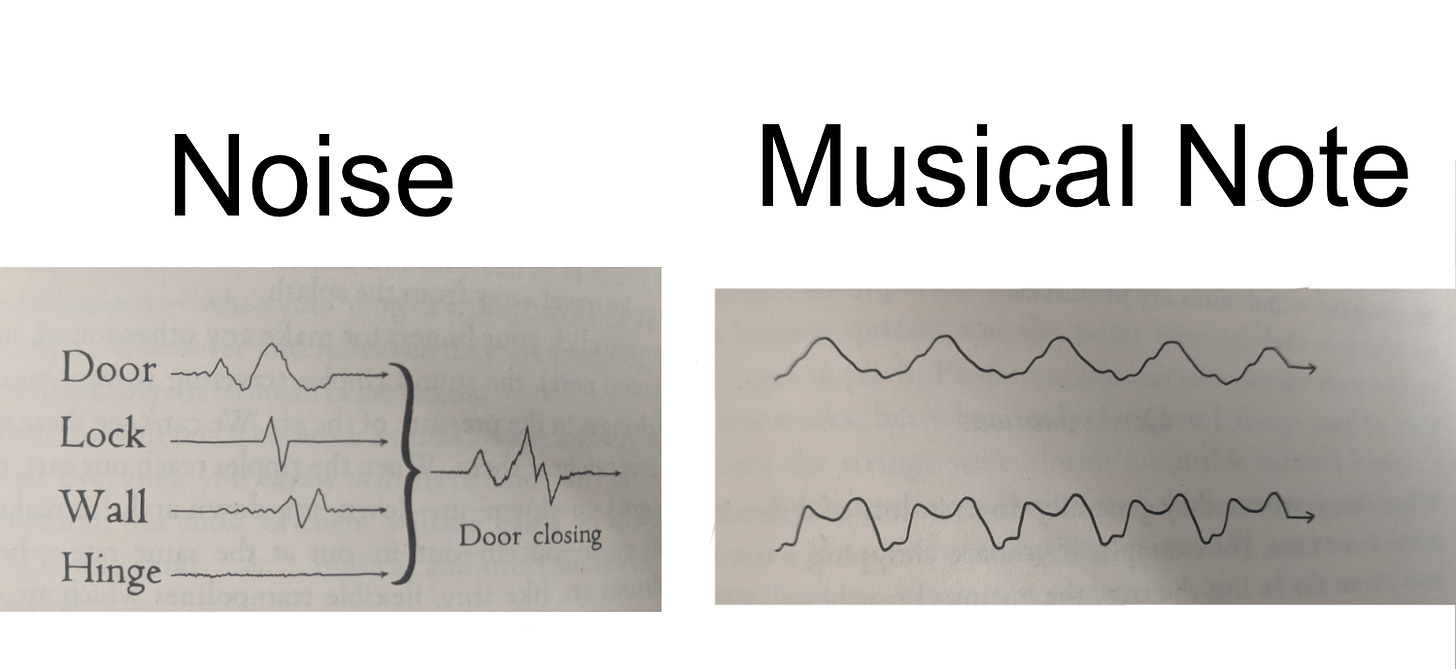

The common understanding of Noise is that it is any sound the listener finds unpleasant: a screeching subway, a barking dog, or Pop music you don’t like; but the scientific definition of Noise is much nerdier. In physicist and composer John Powell’s book How Music Works, these handy graphics clearly distinguish the difference between a noise and a musical note.

Noise is a chaotic ripple of vibration that is the combination of multiple sounds forming an uneven wave. A musical note, on the other hand, is a sound wave that features a distinct pattern that repeats between 20 and 20,000 times per second. The musical note can appear to be complicated, but as long as it repeats regularly, it is not technically noise. These notes do not need instruments to be produced: a power drill produces a repeated wave, which in turn is a note. Artists have used mechanical tools to create sounds that have been incorporated in a musical way, like The Talking Heads in “The Facts of Life,” where a compressed air-drill is part of the instrumentation.

Noise becomes music when artists experiment with these chaotic sounds to push the boundaries of what we consider to be “music.” If Pop is the thesis, then Noise is the anti-thesis. Eventually the tension between them collapses to create a synthesis of the two. In this event, the synthesis instantly becomes the new Pop thesis, and Noise artists must explore new sonic frontiers to develop an updated anti-thesis. This cycle has played out for the entirety of music history: Rock’n’Roll, Hip-Hop, Electronic, and Industrial were all once considered Noise, but became synthesized (and $monetized$) into the Pop canon. This is the nature of human cultural progress: the fusion of two inherently conflicting concepts lead to a new order (for more on this, German philosopher Johann Fichte is your guy).

We cannot understand or identify Pop music without the contradiction of Noise, and vice versa. Our brains interpret every sound as either Pop or Noise in the same way they identify Day and Night.

The 5,071 Genres

I hope you enjoy your Spotify Wrapped and you continue to experience new styles of music in 2021. Remember to purchase physical copies or merch from your Top Artists. If there truly are 5,071 genres, then it’s safe to say that we are limitless in our potential to create new sounds and challenge our current understanding of “music.” We all have our preferred sub-genres, but a quick glance at the Every Noise scatterplot reveals their deep connection to one another. Rock is only a skip away from Electronic, which is only a hop away from Reggae. It’s all the same thing. It’s all Pop.

Thanks for reading! I’d love it if you shared or recommended Transmission to your friends, colleagues, and exes. Subscribe so you never miss an edition! You can even leave a comment! I might roll out a mailbag feature responding to comments, critiques, and slander. Here are the buttons associated with each interactive activity: